Immigrants: Home of the Brave

Immigrants: Home of the Brave

Dare to dream the American dream? Real stories bring to life the bravery, sacrifice, and hope that has defined every wave of US immigration—including, most likely, those of your ancestors.

Featured guests: Sonia Sanchez, Nimisha Ladva, Grant Hollis, Catzie and Aditi Vilayphonh, Ross Gay, Sreedevi Sripathy, and Rebekah Rickards

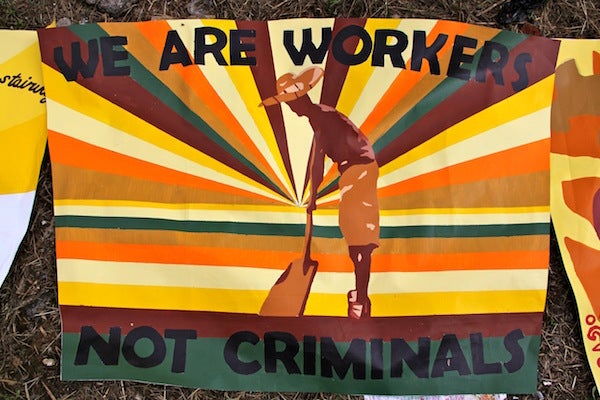

Banner image: Neil Santos

Of Thee I Sing

Borders can't contain the creative spirit of our cultures. From blues to punk, Irish ballads to hip hop, and much more, hear how where we come from breathes new life into art through immigrant music and poetry.

Painting the Journey

Visual artist Michelle Angela Ortiz celebrates her family's immigrant roots by lifting up immigrant narratives in vivid murals across Philadelphia.

Read the transcript

HOME OF THE BRAVE TRANSCRIPT

MIKE VILLERS: From WHYY in Philadelphia, this is Commonspace, a collaboration between First Person Arts and WHYY.

JAIME J: Welcome to Commonspace, I’m your host Jamie J of First Person Arts…and this is a place where real life stories speak to the pressing issues of our times…

IMMIGRATION MONTAGE

JAMIE J: Immigration is all over the news, and I’m feeling a little bombarded by the headlines. But don’t worry, no matter what the news cycle brings, we’re here at Commonspace, with story tellers, poets, and ‘round-table talk with the Commonspace crew and special guests, to delve a little bit deeper into the immigration debate.

JAIME J: You know, the port of entry at Ellis Island, with its famous statue of Lady Liberty, is where so many of our immigrant stories began. And today, I’m visiting the home of one of America’s great poets, and someone I’m blessed to call my friend, Sonia Sanchez, to begin our show on immigration, called “Home Of The Brave”, with a special reading. Hello Sister Sonia…

SONIA SANCHEZ: How you doing my dear sister?

JAMIE J: When I think of immigration I think of that lady standing in the New York Harbor with that torch in her hand. Now, you’re known across the world for writing 17 books of poetry, but also for your iconic reading style. Would you read for us the poem etched in the base of the statue of liberty to start out our conversation about immigration?

SONIA SANCHEZ: That would be an honor to read the piece. It’s called “The New Colossus”, by Emma Lazarus.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

JAMIE J: Thank you Sister Sonia. Now let’s go back to WHYY for more Commonspace.

JAMIE J: The mother of exiles. We know her as the Statue of Liberty. She’s still a powerful symbol, but my question is, has the promise of welcoming people to our shores ever been an easy one to achieve? I mean, what really happens once you get here?

DAN GASIEWSKI: Prejudice. They face prejudice. Every wave of immigrants has been dehumanized and told that they were gonna destroy America.

JAMIE J: Ok, by the way everybody, that’s Dan Gasiewski of First Person Arts…

DAN GASIEWSKI: They were told there was no way that they would ever adapt and become a part of the United States, and when you look back at it, it seems silly to say “Oh, the Irish will never become part of the United States, they’ll never integrate.”

For Ben Franklin to say ”Oh, those dark skinned Germans can no sooner become American than they can change the complexion of their skin...”

JAIME J: Wait a minute, Dan…Are you telling me that at one point German people were considered dark skinned?

DAN GASIEWSKI: Well, some of them. This is from something that Ben Franklin wrote in 1753 - so this is even before the Declaration of Independence. Here we go: ”Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a colony of aliens, who will shortly become so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them - and will never adopt to our language or customs any more than they can acquire our complexion.”

That’s Ben Franklin.

JAMIE J: WOW…

DAN GASIEWSKI: Yeah. And to the second point the next paragraph that he says is, “Which leads me to add one remark, that the number of purely white people in the world is proportionately very small.” So he is calling Germans…

DAN AND JAMIE J: Non-white.

DAN: And that’s something that happened all the time. The Irish were non-white. Mexicans were considered white, according to law, before Irish people were.

JAMIE J: So to Ben Franklin, Germans were not European, or they weren’t “white.” Their skin color was something different.

DAN GASIEWSKI: Basically there were white Germans and non-white Germans. Which is something we would not even recognize today.

JAMIE J: And that was Ben Franklin…

DAN GASIEWSKI: Um-hm…That’s how deep it goes.

JAMIE J: By the way, I’m Jamie J and you’re listening to Home Of The Brave on Commonspace. And today we’re inspired by real-life experiences of immigration. Hey, check out this mix…

(MUSIC)

JAMIE J: That was a remix of The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Big Poppa”, called “I’m Just An Immigrant,” from Mr. Wilder productions. Now you know, the journey of immigrants has always rested on hope for a better life. But that hope - like the kind we just heard expressed in that song - often runs smack dab up against the legal entanglements of our immigration system. I’m thinking of the case of Nimisha Ladva, who told her story at a recent First Person Arts story event.

NIMISHA LADVA: So I’m going to tell you the story of how I became an American. This is the real story, it’s the one that I’ve never told in public until today. It starts when I was 21 years old. I’m a senior at UCLA. It’s tank top weather, but I’m wearing jeans and long sleeves because I’m kind of awkward and self-conscious, and very much the daughter of my immigrant parents.

I am so naïve and inexperienced, I’ve actually never had a beer.

But on this day, I’m in Los Angeles Federal Court, and I am in the basement, and I’m being arrested for the second time. I am an illegal alien and I am turning myself in. When I was 12 years old, my parents came to this country on their visitor visas, fully expecting to over stay, and build a life in this country. My father naively believed that if they just came here, and applied themselves and worked hard, they would find a way to become Americans. That is not how immigration law works in this country. Eventually, they found that there was one possible chance. If they turned themselves in as illegal aliens, we had the right to a hearing. And at that hearing, if the judge said yes, we could stay and become citizens. If he said no, we would have to leave. There would be no going back to the lives we had built in America.

We had to convince the judge on three grounds. One, that we had made meaningful ties to the country. Two, that we had good moral character. And three, that the deportation itself would cause undue harm. There was one problem. Because of my age, I was no longer included in my parent’s “we”.

They had a business here. They employed citizens. They had a child born in this country. I had none of these things. My only chance was to have my case heard on the same day by the same judge, and hope that the strength of my parent’s case would inform the decision made on mine. But my paperwork got lost after my first arrest. And that’s how I found myself in the basement of LA Federal Court.

I should tell you that the basement also doubles as the jail. So when I’m down there my arresting office asks me to button my shirt all the way up to my collar. And then he leads me past men in shackles who thrust their hips at me obscenely. They are close enough that they can lick the air around me. My mug shot is so small you cannot see the cold sweat of fear on my face.

It takes two years. But my date arrives. Our attorney informs me that in Los Angeles there are seven judges who sit on the federal immigration bench. Three of them, he tells us, they are just looking for a reason to let you stay. The other three, they need to be convinced that we have a pretty good case. The last one…the last one he tells us has a nickname. He’s called The Hanging Judge”.

On the day of our hearing we’re gathered in the cafeteria. My dad is working the room, because we’ve invited people to come and support us. And I’m looking around and he’s giving coffee in foam cups to people. And I see, I see my roommate and her mother, I see the retired teacher couple, who gave my parents money when we ran out. The husband, he’s an avid hunter, a Republican and an NRA supporter. My parents, they’re pretty liberal, and they’re lifelong vegetarians. But these are the people who saved us. And then I see my attorney, and he walks in. Listen, he says, “We got the hanging judge.”

There’s no going back now, we have to get to court. It’s noisy to move thirty people from the cafeteria to the courtrooms. So people are starting to come out of their cubicles and their offices wondering what’s going on. It turns out it’s pretty unusual to have thirty people show up to a deportation hearing. Our attorney takes it upon himself to walk through the hallways announcing “Hey all these people here today, they’re here for my clients…this family.”

And we’re marching down to the courtroom. My dad is holding the door open so people come in and suddenly there’s a loud voice behind him.

“SHUT THE DOOR!!!”

We turn around…it’s the judge. He’s already angry. My dad lets go of the door and sits down as he is told to do so. The judge is looking at the paper work. The first thing he says:

“These people are immediately deportable. There’s no reason for a hearing here today. Why are you wasting my time?” the prosecuting attorney, who represents the Immigration and Naturalization Service stands up “Your honor, in light of the people who have shown up for this case today, I think we should hear it. The judge grumbles, but he lets the bailiff call order, and my dad takes the stand. He answers some questions. Witnesses are called. A psychologist takes the stand. He talks about my brother. He’s eight years old and he’s having nightmares, because he’s afraid he’s going to be separated from his family. That we will abandon him.

So the judge is upset, and he tells my dad to sit down. He says that’s enough, he doesn’t want to hear anything else. Then he looks up from the papers, and it’s clear he’s made a decision.

“Well, he said, in light of all these people you’ve stuffed in my courtroom today, the deportation is cancelled.”

It’s amazing! People get up, they’re screaming, they’re shouting they’re crying. Everyone is so happy. Everyone is crying except me, because I realize he’s taken my case in his hand…

JAIME J: OK, don’t worry – later in the show we’ll have the conclusion of Nimisha Ladva’s literal “trial and tribulation” in the U.S. immigration system…I’m Jaime J, and you’re listening to Commonspace on WHYY.

: Hey again beautiful ones…I’m your host Jaime J, and we’re here at WHYY, table talking with the First Person Arts and WHYY Commonspace team: that’s Becca Jennings…Dan Gasiewski, whom you’ve already heard from, and Jen Cleary. Also with us is WHYY’s Mike Villers and Elisabeth Perez-Luna.

ELISABETH PEREZ-LUNA: “Let’s assume that there’s a person who really doesn’t want to have anything to do with immigrants…it bothers them…they’re Americans, this thing just goes against the grain. Can you spend a whole day in which you would have absolutely no contact with any immigrant anywhere you go?

MIKE VILLERS: Not in Philadelphia!

DAN GASIEWSKI: Probably not the east coast, and probably not the west coast.

ELISABETH PEREZ-LUNA: So where would you encounter, where would be your point of contact with different immigrants?

JAMIE J: Oh my God it could be anywhere it could be anywhere it could be your doctor, your lawyer. It could be your cab driver, it could be your guy at the gas pump. You know they could be anywhere.

BECCA JENNINGS: Could be your mirror.

MIKE VILLERS: Could be your boss.

JAMIE J: Could be in your mirror, could be your boss…

ELISABETH: Yes!

JAMIE J: Immigrant people are at every level of society contributing amazing things…

(MUSIC)

I’m Jaime J and we’re here talking about immigration stories. Well if there’s one guiding principle to Commonspace, it’s this: everybody has a story to tell. Here’s Grant Hollis.

GRANT HOLLIS: So there I was, minding my own business in New Jersey. One thing about New Jersey, for those of you who are not Jersey residents, is that you cannot pump your own gas in New Jersey. Have you guys heard this? This is why there are bumper stickers that say “Jersey girls don’t pump gas.” Because they’re not permitted, in fact no one is, you show up to the pump, and you kind of have to stick your credit card out the window, and the guy picks it up and goes and puts gas in your car. And really you don’t care all that much because at the end of the day you don’t care that much because it’s not really all that emasculating because you didn’t really wanna pump your own gas anyway.

So I was coming home from class, and I looked at my gas tank, I needed to stop for gas, I pulled over, and it had not been a very good day at class in particular. I had felt stupid on a number of different occasions and was not exactly in my happy Zen place.

The person came, and took my credit card, and I handed it out the window and I was kind of in my own little zone, and he went and started pumping gas, and after a little bit of time I started hearing water. And I looked and found that the gas nozzle was in my car but it was just pouring out on the sidewalk right then and there. And the guy realized this and he ran over really apologetically, and he was kind of like, “I’m so sorry, here, let me fix this.” And I, being in a really patient mood as you can imagine at that point, said “No. Just let it be.”

Which at one level, is a really nice surface-y thing that really doesn’t mean anything that bad. But underneath what it really said was “You imbecile, you’re a really poor gas attendant and I really don’t like you.”

And I drove home and I had that feeling in my stomach, you know that very healthy feeling of guilt, when you know you’ve hurt a person, and you know that it wasn’t the right thing to do. And I got home and I really felt awful, and I really am thankful that that exists in me. The next week after class I went back to the same gas station, and I showed up and the same guy was there, and I thought to myself, “Oh, please, don’t recognize me.” And he showed up, put the gas nozzle in my car started pumping my gas, and I got out of my car and said “so how’s it going?”

And he said “ehh…fine”.

And I said, “Has your day been busy?”

“ehh. not very busy…”

And you could see in his mind he’s used to being treated like a machine. And I said “So how long have you been working here?” and you can see him pause.

“About three months,” he said.

“Oh, really? How did you get started?”

“Well,” he said, “I’m from Afghanistan, and I came over here.” And he proceeded to tell me a story about the chaos he was living through in Afghanistan. ‘Cause it was kind of a chaotic place, it probably still is a chaotic place. And he told me this really complicated story that I didn’t really understand about how he got to the United States and got in maybe sort of legally. And he came to the states and was trying with his family, to find a place to find a job so he could pay for things, and the only job he could get with his English not being superb, and the fact that he really didn’t really have exactly real citizenship, was a job pumping gas for people in New Jersey.

And about that time, in the fuel booth where, you know, they have the credit card machine and everything, a head pops up. And this head, it belongs to his son, and his son says “Hey daddy!”

He goes “Hey, I’d like to introduce you to my son, his name is Shaheen.” And Shaheen comes out of there, this little second grader, comes out of there, and he says “I’m good at math!”

Because of course he is. And he comes and brings his work sheet, and he says “This one is tricky, and he points at six plus six.” Which is a tricky one, it’s greater than ten. And about that time, I start hearing liquid again, because the gas tank once again overflowed.

And he said I am sorry, I am so sorry. And he winced, and dug trashcan and found an empty pop bottle, and went and filled it up with the windshield wiper fluid and washed off my car by hand with windshield wiper fluid from this trash pop bottle.

I was rather touched, and I said what is your name? He said his name was Abdul, and after that every week I would stop by to get gas at exactly that place. I would make sure that even if I didn’t need gas I would go and get gas, just so I could go and talk to Abdul, and see Shaheen, most of the time, and hear how school was, and what life was like in the United States, and hear his stories which were just absolutely absurd. And it made me think that the more you understand that every person is human, the more you understand that everybody has a story worth telling. Thank you very much.

JAMIE J: Grant Hollis is a frequent performer at First Person Arts slams. You’re listening to Home Of The Brave on Commonspace, a collaboration between WHYY and First Person Arts, and it’s supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage.

(BREAK)

JAIME J: This is Home Of The Brave on Commonspace, at WHYY, and today we’re inspired by real life stories of immigration. I’m Jamie J.

(Music)

JAIME J: And there’s another verse of “I’m Just An Immigrant,” You know, when I hear it, it makes me think this is a land of immigrants – truthfully all of us came from somewhere here except for the indigenous people -- but at what point does one stop being an immigrant, and start being an American?

BECCA JENNINGS: So, my family, the majority of our heritage is Scottish and English. But to me I have trouble identifying with people who have a really great pride in a nationality that, you know, where they don’t live, that is so distant by generations…we just haven’t maintained that sense of culture. I mean, we have a Jennings kilt…you know, and like somebody went on vacation to Scotland, and came back, and the whole family now has like this certain plaid of a hat with a pompom on it, and a kilt, and we’re all decked out…but aside from the costuming, which sits and collects dust in the attic, we don’t really have an emotional connection to that, you know…we don’t have, you know, an Irish flag as a bumper sticker, or you know, so…I have trouble, like, relating.

JAMIE J: That was Becca Jennings from First Person Arts. When we have this immigration conversation, it’s generally from the perspective of how Americans feel about immigrants. We rarely have a conversation or we certainly don’t have enough conversation about what it feels like to be here form some place else.

(MUSIC)

JAIME J: That was Karmacy, with their hit single “Outcasted”. Like the rapper in the song our ‘HYY colleague…

SREEDEVI SRIPATHY: Sreedevi Sripathy.

JAMIE J: …was born in 1977. She is a first generation South Indian whose parents emigrated in the seventies. So Sreedevi…what was it like growing up in an immigrant household?

SREEDEVI SRIPATHY: “You know the word immigrant’s really interesting when I think about it…because I never really had this relationship that I’ve ever thought of myself as a daughter of immigrants, even. I’ve been here my whole life. I consider myself so very American. But when I think about it there were some really key differences about what it was like to grow up in that household and then walk out this door into this very American world. You know we had certain customs and certain values and traditions that we would do, and I would walk out and realize oh, wait, not everybody else is doing the same thing that I’m doing.

And then it also became something that I got made a lot of fun about. You know a lot of people mocked me about being Indian.

I remember being in middle school, and, you know, there was this movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom that came out, and there was this iconic scene of Indian people eating monkey brains.

And I just remember how many kids would come up to me and asking if I ate monkey brains all the time. And you know everyone gets mocked in middle school for something. But when it’s the color of your skin? Like, there was no way the brown was coming off. Whereas with other kids maybe they could at some point lose the weight , maybe they could get rid of the glasses and get the contact lenses, maybe their hair would grow out, maybe they would grow taller…but for me there really actually no escaping that.

JAIME J: Wow…was there ever a time when you didn’t feel like “the other”?

SREEDEVI SRIPATHY: You know actually it’s really funny, I’m from California, and I lived in Silicon Valley, so in the 90s there was this huge tech boom and a lot of immigrants from India were coming over, a lot of Indian engineers. And I remember at one point going to a movie theater, just a regular old American movie theater showing, like, an American movie, they weren’t showing an Indian movie…and the lights come up and I look around and everybody around me is Indian and I just remember going “Wait, what just happened? Am I in India? Like, where am I? I had never seen that many people who looked like me in my life. It was the first time I started experiencing kind of this larger, larger Indian community around me and going everywhere and seeing so many different people who looked like me. It was really cool actually.

JAIME J: Thank you Sreedevi Sripathy for your stories.

SREEDEVI SRIPATHY: Thank you.

JAMIE J: Now we’ve held you all in suspense long enough…so let’s get back to Nimisha Ladva’s journey through the US immigration court system. You’ll remember that when we left her, the quote-un-quote “hanging judge” had ruled that Nimisha’s mother, father, and younger brother could stay in America…and her supporters in the room were overjoyed.

NIMISHA LADVA: It’s amazing! People get up, they’re screaming, they’re shouting they’re crying. Everyone is so happy. Everyone is crying except me, because I realize he’s taken my case in his hand…and the first thing he does is slam it to the bench.

“You’re kidding me, right? You’re kidding me because, like, this case? This case has truly no merit.”

My attorney gets up, “Your honor, it’s clear that this young lady is part of the family we just heard from. She’s just had a few birthdays and her case has to be heard separately.

“You think this is a birthday party for the girl? Let me ask you a question, attorney, how long have you been an attorney in this country?”

My lawyer is dangerously red in the face. But the INS prosecuting attorney stands up. “I think we should hear this case.”

So I’m called to the stand, I take an oath to promise to tell the truth. The prosecutor asks me some questions about what I’ve been doing, and I tell them that I’ve been a student at UCLA. He asks me if I’ve ever had a job here, and I start to sweat. The truth is, for the last few months at UCLA, I took an office job.

I want to explain that I am really sorry I did that. I was applying to graduate school and I didn’t have money for my applications. I want to explain that for the four years I have been at UCLA, I have been borrowing my roommate’s clothes and just for once I wanted to have my own jacket in my own size. I am so scared. The judge asks me to answer the question.

Have you worked in this country illegally?”

“Yes, sir, I have.”

I see my father’s face, he bows his head, he didn’t know. My attorney gets up to offer some character witnesses, the judge tells him to sit back down. I am so afraid. Where will they send me? Will they send me to India, where my ancestors are from? I’ve never lived there. Will they send me to Kenya? I was six weeks old when my parents moved from Kenya to England. And then I realize they’ll send me to England, where I can be a Paki again. Where I can be the brown girl on the bus that no one will sit next to.

The judge calls the attorneys to the bench, and sends them to sit back down. I’m all alone on the stand. I’m looking out at the people who have shown up for me today, on that day. They are white, they are black, they are Mexican, some are educated, some are rich, some are working class. They are all strivers, they are all dreamers, they are all American.

I look at the judge. I can tell he’s made his decision. This way, or that way…stay or go. Who will I be without a home. Without my family, without my friends. And then I see that the judge is looking at the people as well.

“The order to deport is cancelled.”

I am so excited I finally let my tears fall. I’m finally home.

(applause)

JAMIE J: I’m Jamie J, and you’re listening to Home Of The Brave on Commonspace at WHYY…

(BREAK)

JAMIE J: I’m Jamie J, this is Home Of The Brave on Commonspace at WHYY. So now you’re here. What’s the next hurdle that immigrants have to clear? The language hurdle. We at Commonspace are blessed to have two beautiful Latinas on our Commonspace team. Elisabeth Perez-Luna from WHYY, and Jen Cleary, from First Person Arts. One born in America, and one not. Now Jen…Jen Cleary does not sound like a Latina name…

JEN CLEARY: No…I know…because my name is Jennifer Cleary Rubinos Gil.

JAMIE J: Well I’ve heard that your name is not Jennifer inside your house…

JEN CLEARY: No, it’s not…my grandmother refers to me as “Yennifer”…she can’t pronounce my name, there’s no way to say that right. I mean, I remember being a kid, and we’d go out to run errands with my Abuelita, and we’d be in a store, and my grandmom does not speak English. She’s been here since the 50s, so we speak Spanglish to each other all the time…and I remember when we’d be in a store, and I’d speak Spanglish to her she’d tell me “don’t talk to me like that outside the house”, because we’d get treated differently regardless of their background. And you know we’d be in a restaurant and it’s usually my mom myself and my grandmother, and we’ll sit at the table and my mom would usually just order for my grandmother, because she can’t order in English, and there’s that…I don’t know exactly how to say it but you do get treated differently when you don’t have access to English, and people look down on you, especially a woman been here for a really long time she’ll get a lot of hardship, even from me as a kid. You know, I used to get on her a bit because she still doesn’t know English. And now that I’m older I understand better the implications of coming to this country and educational levels, and all these things that occur. But you can’t stop people from treating you differently when you don’t know English.

JAMIE J: Now Elisabeth, conversely, you have a Latina name, Elisabeth Perez-Luna, and you have what we all consider an accent…how does that make your experience different from Jen’s?

ELISABETH PEREZ-LUNA: Well, I remember that people felt a little bit weird, because I do have an accent, obviously, but it’s not completely defined, you know, so…my mother was French, so we spoke French at home…spoke Spanish to of course, when I lived in Latin America. I’ve been here most of my life. But I relate to Jennifer’s story, because I have a friend who practices keeping his accent, because he thinks it defines him. So accents are complicated. But it’s very funny because I’m a radio producer, and I always hear people telling me, oh I wish I could hear your reports, but I don’t speak Spanish And I think it’s funny because I don’t produce anything in Spanish. So it’s the assumption of your name and the slight accents. I don’t think it’s malicious; it’s not understanding that this is a complex country. So, I really think that I’m very American, because this is what our colleagues are surrounded with…we are all dealing with enriching the language with words and accents. And there’s something very beautiful about that. And I’m very proud to be what I am, accent or no accent, mijita!

JAMIE J: (Laughter) Perfect.

JAMIE J: Catzie Vilayphonh is the middle member of a household of three generations of Lao women. She told a story at a Translation Slam about her Lao family and the layers of languages each family member has to navigate. They speak varying degrees of Lao and English in the household – or as the family refers to it – Lao-lish.

CATZIE VILAYPHONH: For all intents and purposes of this story, I speak two languages, English obviously, and Lao. Language for me is very important. It remains one of the effective ways to communicate if done properly. Ever notice when you go to a restaurant and pronounce the food right, the kind of treatment you get? There are certain words and phrases that cannot be precisely translated into English, and to be honest, there are certain words and phrases that just sound better in other languages.

But language, especially for diaspora born children keeps us closer to a culture we may not be exposed to anymore, a country we may never visit again, and family members we may never meet.

I live with my mom and daughter Aditi. My mother speaks Lao and very little English, and Aditi speaks English but very little Lao. I was raised speaking Lao to my mom, so that is what I speak with her. With my daughter I use English, because that is the language I’m more fluent in and therefore more comfortable with. Yet when they speak to each other they use a completely different language. Broken English.

(Audio recording)

Catzie: Aditi tell me about tomorrow, what you’re doing for international day.

Aditi: Um, we’re going to bring food.

Catzie: What kind of food?

Aditi: Sticky rice, and we’re going to make 25.

Catzie: Who’s making them?

Aditi: My grandma.

Catzie: Is she making it right now?

Aditi: No, she’s going to make it at nine-o-clock tomorrow.

Catzie: Can you ask her what she’s doing right now?

Aditi: Okay. (Lao word) What you do right now?

Grandma: What?

Aditi: What you do?

Grandma: I clean every day. You don’t (inaudible) help me clean okay? Too much dirty.

Aditi: She said, um, she’s cleaning.

Grandma: Now everything…I tell you. You listen to me.

CATZIE: So technically, broken English is not a language. It’s still English, just with an accent and few extra grammar rules removed. For people like my Mom, it is speaking English, the best way they know how. For my daughter, it’s an intermediate level of understanding.

Listening to her navigate between the English she uses with me and the version she uses with my mom, is an obvious attempt for her to relate. Unlike the mock English that American actors generically use to portray racist characters in movies, which by the way gets played out in real life situations, the broken English my daughter speaks is a well observed imitation. A sound for sound copy of what she hears when my mother speaks. It’s another means to communicate with someone, someone she happens to love.

When my daughter was born I had assumed that my mom would teach her to speak Lao as she had with me. At first it seemed it was going that way. Aditi’s first recognizable word was (Lao word) which is the Lao equivalent to the Yiddish “Oy Vey”. Her first English word, which showed up some months later, was meatball.

But as time passed and watching cartoons became a daily habit, English soon surpassed Lao, and my mom gave in or gave up depending on how you look at it.

So there were a few factors as to why three generations living under one house do not share a common language or why two of them choose a vernacular that isn’t easy for either of them to speak.

First, the transition between Lao to English can be tricky. Lao is a tonal language. So meanings are dependent on the tone. For example (three Lao words) to an unfamiliar ear, may sound like the same word repeated three times. But in actuality what I’m saying in Lao are the words for scratch, proceed and the number nine respectively.

The Vientiane dialect, which my mother speaks, has six tones: low, mid, high, rising, high falling and low falling. At six years old, Aditi cannot differentiate this. And when I try to explain to her the separate meaning for each same sounding word it sounds like a trick question waiting to happen.

Secondly, there is no need for Lao. When I was a child, as far back as I can remember, which was about the age of 5, I was my mother’s translator for everything. I share this distinctive trait with all children of immigrants, particularly and especially because my parents were refugees. In their decision to leave Laos during war, there was no prepping or preparing, no time to learn a new language. I suppose it’s an innate belief of refugees that if you can get by with very little, then you can survive.

My mom and Aditi still have their routine. In the meantime I’ve expected this Lao-lish is how they talk to each other. This secret language amongst family that others try to duplicate but cannot decode. There’s some folks who will tell you, I love yous are for white people. This may be true. But, to that, I say, (Lao phrase) or as my mom and Aditi would put it (Lao-lish version).

Thank you.

***

JAIME J: It is a truly creative and innovative way that many immigrant households, with several generations under a roof, work with and shape the language so that they can communicate. I think about Lao-lish, Spanglish words, Yiddish expressions, and so on…they swirl around us and enrich our language. Add to it the rich inventiveness of African American idioms, and how we have shaped the language to work for us, and that’s what speaking “American” is all about -- and it’s beautiful…

JAMIE J: This is Home Of The Brave on Commonspace at WHYY, I’m your host, Jamie J, and we’re talking about immigrant life. So we invited writer Ross Gay to share his poem about a real immigrant story – one that could only happen in Philly.

ROSS GAY:

To the Fig Tree on Ninth and Christian

Tumbling through the

city in my

mind without once

looking up

the racket in

the lugwork probably

rehearsing some

stupid thing I

said or did

some crime or

other the city they

say is a lonely

place until yes

the sound of sweeping

and a woman

yes with a

broom beneath

which you are now

too the canopy

of a fig its

arms pulling the

September sun to it

and she

has a hose too

and so works hard

rinsing and scrubbing

the walk

lest some poor sod

slip on the silk

of a fig

and break his hip

and not probably

reach over to gobble up

the perpetrator

the light catches

the veins in her hands

when I ask about

the tree they

flutter in the air and

she says take

as much as

you can

help me

so I load my

pockets and mouth

and she points

to the step-ladder against

the wall to

mean more but

I was without a

sack so my meager

plunder would have to

suffice and an old woman

whom gravity

was pulling into

the earth loosed one

from a low slung

branch and its eye

wept like hers

which she dabbed

with a kerchief as she

cleaved the fig with

what remained of her

teeth and soon there were

eight or nine

people gathered beneath

the tree looking into

it like a constellation pointing

do you see it

and I am tall and so

good for these things

and a bald man even

told me so

when I grabbed three

or four for

him reaching into the

giddy throngs of

wasps sugar

stoned which he only

pointed to smiling and

rubbing his stomach

I mean he was really rubbing his stomach

it was hot his

head shone while he

offered recipes to the

group using words which

I couldn’t understand and besides

I was a little

tipsy on the dance

of the velvety heart rolling

in my mouth

pulling me down and

down into the

oldest countries of my

body where I ate my first fig

from the hand of a man who escaped his country

by swimming through the night

and maybe

never said more than

five words to me

at once but gave me

figs and a man on his way

to work hops twice

to reach at last his

fig which he smiles at and calls

baby, c’mere baby,

he says and blows a kiss

to the tree which everyone knows

cannot grow this far north

being Mediterranean

and favoring the rocky, sun-baked soils

of Jordan and Sicily

but no one told the fig tree

or the immigrants

there is a way

the fig tree grows

in groves it wants,

it seems, to hold us,

yes I am anthropomorphizing

goddammit I have twice

in the last thirty seconds

rubbed my sweaty

forearm into someone else’s

sweaty shoulder

gleeful eating out of each other’s hands

on Christian St.

in Philadelphia a city like most

which has murdered its own

people

this is true

we are feeding each other

from a tree

at the corner of Christian and 9th

strangers maybe

never again.

JAIME J: You know it’s very interesting this business of being an American. And it requires adaptive skills for everybody, whether you were born here or not. It’s navigating language and customs, balancing traditions and memories, and more often than not I think we all, at the end of the day, are all proud to be part of this country. Which leads me at a funny story I really love: Rebekah Rickards’ “Life line”.

REBEKAH RICKARDS: So, um every artist I’ve ever known has had one, at least one of two terrible jobs. They’ve either worked as a barista at some pretentious coffee shop or a camp counselor at you know some underfunded and overpopulated terrible summer camp with some badass kids. It just always happens. And, uh, fortunately for me, five years ago, my first summer here in Philly I worked both of those jobs at the same time.

So every day I would wake up and I would bike into Center City and I would work from 5 am to Noon serving coffee. And then I would bike back west and I would work with the kids from lunchtime until 6 pm. And lunchtime was complicated because it was a really poor district so sometimes the food truck just wouldn’t show up and these kids would have no lunch.

Or even worse, like the food would come but it would be spoiled from sitting in the heat for so long. And so I would have to like immediately confiscate all of the juice boxes because they were fermented and these kids would be like getting turnt up on some apple juice. There was always the chubby kid in the corner like hoarding five boxes of juice, like slow sipping, like “Mmm, this is good.”

But, you know, there was no AC in the building and sometimes no lunch so hands down the best part of summer camp was going to the pool. And pool is a generous word because it was literally a concrete dugout that was 2 feet deep all around the pool, so there was no deep end, there was no slides, there was no floats, no toys, no nothing, just knee deep water all around the pool, right, and the pool was super small so we had to like send the kids in like little organized groups and rotate them every 20 minutes, to like, prevent heat stroke.

And so, but that wasn’t the scariest thing about the pool. The scariest thing about the pool no doubt was, um, for whatever reason they felt like they needed a lifeguard, you know in this two feet of water little pool.

So in the corner there was this giant tower, and uh on top of the tower, there was this little five foot nothing Latina lifeguard, her name, I will never forget was Matia Rosa Blanca, and she went by Rosa. And she was terrifying, she was so so scary.

Every time we went there she would make all the kids line up on the edge of the pool, and she would go over her rules, and I swear to God these are her rules I’m gonna try to say them just like her.

She say, “Okay today in my pool, there’s no running, no jumping, no diving, no dancing, no splashing the water in my face, no pissing, and no punching in my pool and if you do I'mma drowned you.” Swear to god she said “I’mma drowned you,” right?

And these kids, and she said, “Okay have lots of fun”, blow the whistle and these kids would like sit there like, oh my god. It would take them three minutes to get in the pool and once they did it took them 10 minutes to figure out how to submerge themselves under the water, ‘cuz they’re like trying to like splash the water like side dip into the water.

And by that time it’s time to rotate, so they blow the whistle and now they’re rotating, and she makes the kids lines up on the pool again - she goes over the rules again. And as they day progresses she adds more and more rules ‘cuz she’s just irritated right?

So she says “Okay, second group, there’s no running, no jumping, no diving, no dancing, no splashing the water in my face, and there’s no pissing, and there’s no punching and if you wash your nasty cheeto hands in the water again, I’mma drowned you.” And so here we go, we get in the pool again…

She wasn’t always mean but like sometimes she tried to be really fun and nice and she would like organize group games. She played a game of uh duck duck goose once which went all kinds of wrong cuz this kid got like donkey kicked in the back of the spine and so like now we’re only allowed to play like duck duck but no goose. So these kids are like standing like “duck, duck duck..” like an endless game of duck duck goose.

But one time yeah, as you can imagine…

And one time Rosa actually did save someone’s life - she really did I saw this. This kid he fell under the water, and he had swallowed a lot of water so he was panicking. And I saw Rosa at the top of her tower, she was texting at the time, and she looked down, she was irritated, kept texting. And then she looked again, she was just annoyed, she was like “Hey, hey just stand up, it’s like two feet of water okay…stupid.” Like oh my god.

So um, you know at the end of the day, like six rotations later she would make everyone line up at the edge of the pool and she would go over her rules again to prepare them for the next day, right. And by this time, there’s like ten new rules, right, she keeps going on, she’s like “Okay so listen tomorrow when you come to my pool, I don’t wanna see no running, no jumping, no diving, no dancing, no splashing the water in my face, no pissing, no punching, no cheeto hands and no donkey kick to the back of the spine, okay, if you do, here I go,” and they all yell “You’ll drowned us,” because by now they know what’s up, right?

And then so she says “Okay everybody grab hands and stand up, I got one more thing to say.” And at this point I’m like real nervous right ‘cuz she gets her megaphone out. I mean I’ve been nervous this whole time but like now I’m extra nervous ‘cuz she has like a megaphone, like oh my god, what’s about to happen. All these kids stand up, she says “Okay everybody repeat after me. I am..” and they say “I am…”, “somebody,” and they say “somebody.” She says “No no no no no. Say it again, I want you to say it like you mean it and say it with pride. I am somebody.” And they all say it out loud. “I am somebody” and, they mean it. And I believed them.

And she says, “You know that’s right, and don’t let nobody tell you otherwise, including myself.” And, it’s so crazy because with all the yelling and all the rules and all of the bad pool games and the death threats, you know, like that is what the kids hung onto, like for real, and you know Rosa taught us, taught us, taught me and the kids, like no matter who you are or where you come from, you are somebody.

And that is exactly the lifeline they needed…so…

(Music)

JAMIE J: I’m Jamie J, and you’ve been listening to Home Of The Brave on Commonspace, a collaboration between First Person Arts and WHYY. On behalf of the entire Commonspace team, thank you so much for joining us to hear our stories. And don’t forget, we’d like to hear yours. Go online to A-Commonspace-dot-org.

— that’s A-commonspace-dot-org. We want to hear from you. Commonspace a place where true stories speak to the pressing issues of our time, it’s produced at WHYY by Mike Villers, with contributions from the First Person Arts Staff, Dan Gasiewski, Becca Jennings, and Jen Cleary. The Executive Producer of Commonspace is Elisabeth Perez-Luna.

Commonspace has been supported by The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. I’m Jamie J Brunson…please call me Jamie J…reminding you – everybody has a story to tell…

JEN CLEARY: So two years ago I’m at the doctor’s office getting a checkup…and the doc says, “tell me about your background”… And I said well my mom is Cuban and my dad is Irish, and she straight up looks at me and said “How did that happen?”

JAMIE J: WOW

JEN CLEARY: I know…so I look at her and I say, “Well sometimes when a man loves a woman very much, they get married and have some babies, and then a couple of years later they’re sitting here in your office…” (laughter)

-END-