Gay Pride and Prejudice

Gay Pride and Prejudice

Parades are celebrating LGBTQ rights around the country. More visibility has increased recognition of gay communities as integral parts of American life. But not for everyone; some still view them with contempt – even aggression and outright violence. Our stories explore both worlds.

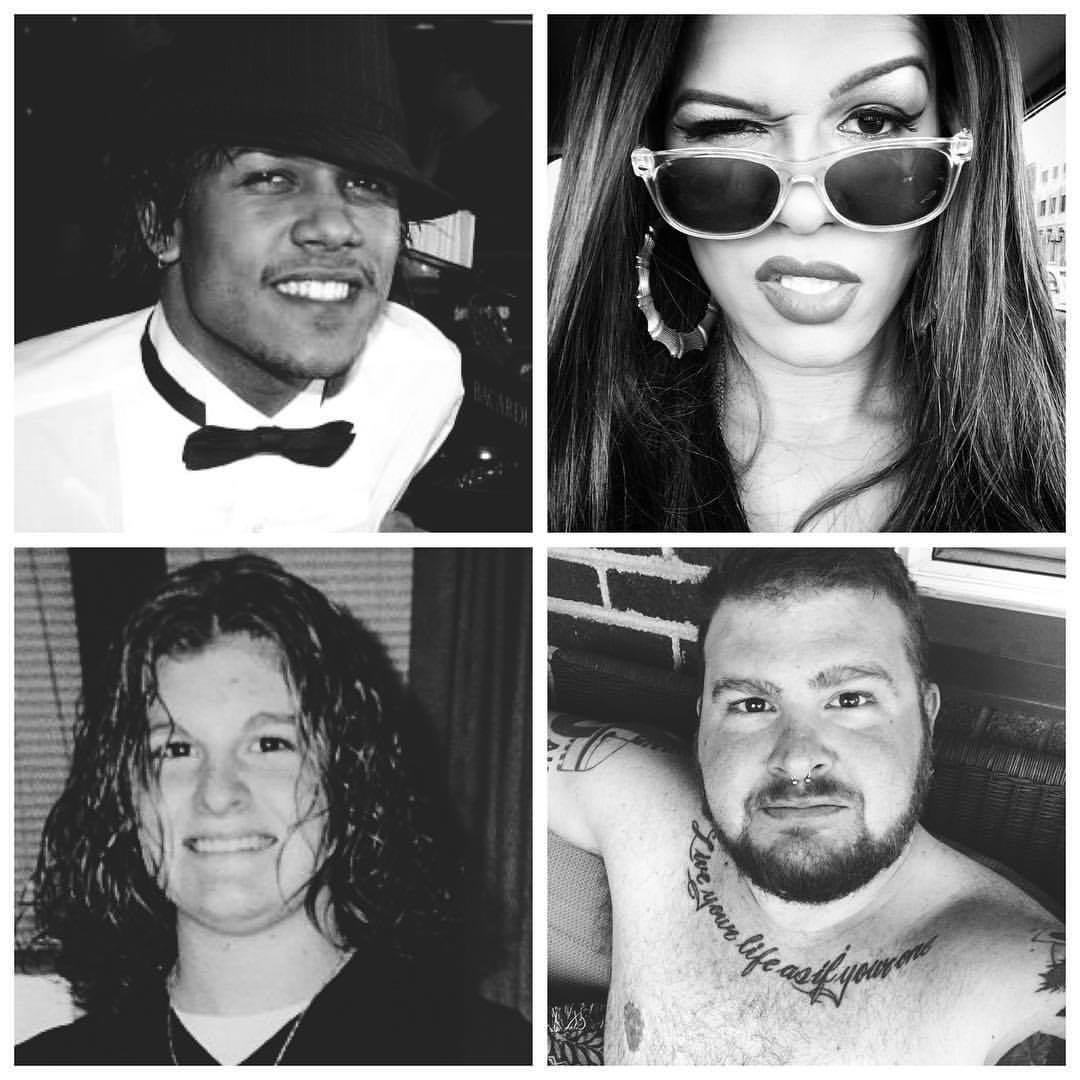

Guests: Anissa Weinraub, Amber Hikes, Aaron Stella, Christian A’Xavier Lovehall, Kylin Mettler, Bea Cordelia, Mark Davis, Jaden Rogers, Gabby Gibson, Vendetta Washington, Charles Tyson Jr.

Photo: Johanna Austin. Slideshow images courtesy of Jaden Rogers and Gabby Gibson.

Wholeheartedly Trans

Love is hard to find at any time, so what are the chances of a transgender marriage commitment? A trans couple opens up about their journey.

It’s Not Easy Being “B”

Bisexuality is neither a fad nor a statement--it’s an identity. Two bisexual people of color talk about their experiences and the complications brought on by society’s discomfort about anything having to do with gender, sexuality and race.

Read the transcript

JAMIE J: From WHYY in Philadelphia, this is Commonspace.

[News reporting from Orlando Shooting]

JAMIE J: It was three things the deadliest mass shooting by a single shooter in US history, the deadliest terror attack in the US since 9/11, and the deadliest incidence of violence against LGBTQ people in US history. 49 People were killed, and 58 people were wounded. And it all happened in one day June 12, 2016 in Orlando, Florida.

I'm your host Jamie J, with WHYY’s Elisabeth Perez Luna and this episode of Commonspace is all about LGBTQ experience.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Yes Jamie, let’s face it, it has never been easy to be a member of the LGBTQ community. Even these days it seems that for every victory in cementing the civil rights for this group, a new act of legislative regression or unspeakable violence tells a different story.

JAMIE J: Just what is it that inspires such rage and anger towards our fellow LGBTQ citizens? Seems to me like we all want the same thing in life to be loved, happy and safe.

Anissa Weinraub told a story that reminds me that in so many ways gay or straight we’re all alike in our need for love. And that first love... mmm... no matter who you are loving, it’s awkward, scary and thrilling all at once. Here’s Anissa.

ANISSA WEINRAUB: So, this is actually about my first ex-girlfriend. And this story starts like many queer women in a high school softball dugout. It was the mid 90s, and I was living in Fort Wayne, Indiana. I was a freshman in high school and the junior varsity team season had already ended, and I got called up to the big leagues to the varsity because they wanted to show me the ropes and let's just say I got shown a few different kinds of ropes that summer.

So, I was in the dugout telling jokes to the other teammates to get them to like me and there was this 6-foot tall, longhaired butch girl kind of super athlete named Kathy Hoverman. And there was something about her that reminded me of this other person I knew Christy Comstock. So real quick Christy Comstock, I met at Jewish Day Camp and she was the first openly queer, gay person that I've ever met and I thought she was so cool, and so smart and so fierce and so hot.

And it was really confusing for me. So there I was in the dugout and I was I don't know what it was it was, maybe her hand gestures or her finely chiseled jaw line. And there was a spark and so I looked at her and said: “You really remind me of my friend Christy Comstock.” The subtext was obvious: Christy is gay, and are you gay? And am I gay? And can we be gay together?

Somehow she didn't realize the subtext and she kinda looked at me like cool and ran out to get her position in center field. And so there I stood in the dugout, kind of peering out over the horizon of my life and she made this really amazing catch like leapt for it and I don't know what it was universe or the goddess but it streamed into me, and out burst “If Kathy Hoverman were gay, I would go for her.” “WHAAAAATTT?!?!?!?”

I looked around and there was only one other person in the dugout, Amanda Munch. That's really her name, Amanda Munch. It's like I'm on The Simpsons or something but that's really her name it's the Midwest. So, Amanda Munch looks at me and says, “I'm totally telling her.” And I took every ounce of conviction and integrity I had and I looked at her and I said: “Do it.”

And in that moment that dusty dugout I took control of the rest of my life. And thus went my summer of courtship. So let me just tell you I was 15, somewhere straddled between Nirvana and the Lilith Fair. A rabid vegetarian, antimilitary, environmentalist and I loved musical theatre. Kathy Hoverman had just graduated high school. She was in the Junior ROTC she wanted to grow up and be either a bomber fighter pilot or professional soccer player so it was a match made in heaven. Every morning, I would strap on my rollerblades and roller blade over to her house and put little love notes on her car and we would go on “friend dates” and I would try to charm her with my quirky precociousness. We both edged nearer and nearer to this attraction, this question mark, but we were both too scared to do anything about it.

Until the end of the summer she was about to go off to college oh I know! And the tension had been building up and building up until it reached this boiling point. She was housesitting for this very, very Christian family that lived in her neighborhood. I mean, I'm telling you people they had on every surface a Bible or cross-stitched saying about sin or Precious Moments figurines featuring heteronormative families.

And she took me on a tour and we ended up in the bedroom. And she looked at me and was like “Do you want a massage?” And I was like “Yes I do.” And so I lay down on this bed covered in a sheet of Jesus fish. And all I remember was the moment of her hands and I don't remember what happened and we were making out and it was it was amazing. Objectively speaking, it was really awkward but it was amazing, right? And it floored me and I ran out of the house and I was frolicking in the summer rain and I was singing “I Kissed A Girl” and I'm not talking about that Katy Perry bulls**t. I’m talking about the authentic, original Jill Sobule feminist anthem. I just watched it on YouTube today guys, it's really something.

Anyway so we broke up. And I could tell you all the stories about how she became my ex, but you know it's really not the point. Today I think the point is that we all have a slew of ex's some of us more than others, and we can always just focus on the negative, heartbreaking, crushing story where we’re dashed of our hopes and dreams about love and then we would really miss these sweet moments. Whether they be in a dusty dugout or an Evangelical bedroom where we find love in a hopeless place. So next year, if I'm not here telling my story about my ex, we’ll know it worked.

JAMIE J: Anissa Weinraub is an educator, organizer, and performer. She told me she spends her days working with teenagers as a high school English and Theater teacher. She also tries to be the queer mentor to her students that she wished she’d had. You can catch her telling stories both onstage at Story Slams and in the streets at protests and marches.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Everyone has a coming out story it’s a rite of passage in LGBTQ life. Let’s welcome our guest Amber Hikes, Philadelphia’s executive director of the Office of LGBT Affairs; she has a vivid memory of her own coming out rite of passage.

AMBER HIKES: So, coming out is a lifelong process and I would say as a femme-identifying person and a femme-presenting person, I have to come out on a regular basis. People assume that I am straight because of how I look. So, I’d come out to my mother in terms of my family first. And it’s a funny story because I didn’t have this whole plan where I was going to come out. I’d been dating a woman for about a year, but it wasn’t until the following January that my mother actually asked me. When I was trying to get off the phone to go to a Super Bowl party, that my girlfriend and I were hosting if I had anything that I wanted to tell her? And I said, “No, we cleared up everything. I told you about finals went, what classes I’m taking, what’s going on with my friends.” “Is there anything you want to tell me personally? About your relationships?” “Oh no, I’m not dating anybody. I’m not seeing anybody.” and she says, “OK. I’m just going to have to walk you through this, I guess.”

JAMIE J: Wow... I’m gonna want to hear how your mother walked you through this, because people that are going to be listening are going to be listening for guidance and be looking up to you.

AMBER HIKES: I’ve heard a lot of coming out stories over the years, and I’m so blessed and honored when I get to hear someone’s process. But I haven’t heard many folk’s parents walk them through it in this way [laughs]. So, I find that this is very unique for me.

So, my mother it was very simple. She actually just wanted me to say, “Mom. I’m gay.” But, I was not ready to say that. So she very literally said, “Ok Just repeat after me.” Mom. “I’m gay.”

What’s interesting now that I think about it is that I never finished that sentence. I never actually said it. I just broke down and bawled. And all I did say was “I’m sorry. I’m so, so sorry. I don’t mean to disappoint you. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.”

JAMIE J: So okay, I want to know why you felt that way and did she agree with you or not?

AMBER HIKES: I felt like I let her down because my mom was an incredibly high achiever. She was very, very impressive several degrees. At the time she was Vice President of Spellman College, which was her alma mater. And was later Vice President of Virginia Tech. And I had done right by her in all things. I was a student athlete and I graduated from college with high honors and had a scholarship. And was doing exactly what she wanted me to do. But, just like most parents, she wanted me to be straight and marry a sweet boy that was equally as successful and become Barack and Michelle Obama the second. And I knew that this was not in the plan that she had for me. I knew that very clearly. Even though I was a straight edge kid, no drinking, no drugs, I still knew that this was a letdown. I was fortunate in that she did not confirm that belief. She said that she loved me no matter what and that she supported me and we were gonna be OK. And she did. And on the other side she was Vice President of a college at the time and her own college was having some issues with hate crimes on their campus. She was VP of student affairs and she brought these issues to me and said this is the response this is my office’s response. These issues this is how we’re going to be supporting the LGBT office and these students and if you were on my campus would you feel validated and supported by these responses or do you think there is something more that I should be doing?

I remember being so proud of her and wishing that I had an ally like that on my campus. It was a beautiful demonstration that coming out reverberates. My coming out helped my mother be a better ally and then effected change for thousands of students on that campus.

JAMIE J: Thanks for sharing your story Amber. You are listening to Commonspace, a collaboration between First Person Arts and WHYY and it’s been supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. I’m your host, Jamie J. with WHYY’s Elisabeth Perez Luna. History tells us our fellow LGBTQ citizens have suffered from banishing and imprisonment to massive annihilation during The Holocaust. Remember, there were pink triangles as well as those yellow stars.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: But tragically, it’s not only the past we’re talking about. I’m thinking of the recent wave of repression in the Russian Republic of Chechnya as reported by the BBC. Gay men have been rounded up in concentration camps tortured and even killed.

[Audio from BBC]

JAMIE J: Yeah, right. And if there are no LGBTQ people, there can’t be violence against them, right?! Tell that to Aaron Stella who has a story about a chance gone way bad in Coleman, Alabama.

AARON STELLA: Let’s set the wayback machine to Alabama, I believe this was the year 2002. I’m walking home from school this day. It is late in the evening—it’s already dark. And I’m going to the community playhouse where I’m going to participate in one of the community plays there for Coleman, Alabama. This is a completely Germanfounded town and if you can’t tell I’m rather Jewish looking so I can only be cast as the narrator for the story, funny enough.

Anyway, on my walk home I encounter this sort of young, waifish-looking boy. Kind of cute in a way, foppish hair and still very wraith like and thin, kind of small. He approaches me and he says, “Listen, would you mind walking me to the backend of my house, which is a little bit farther across this park called Heritage Park which is in Coleman, Alabama.” And I said, “Yeah, sure. It’s fine.” So we get to walk. It’s a rather warm night and you know, me being an openly gay man now here in Coleman, Alabama, probably not the best idea, I begin to somewhat flirt with him. He’s a nice guy and we have a somewhat lively conversation. Well, as we begin to reach the opposite periphery of Heritage Park suddenly he runs off into the distance and I can’t see him. I can barely make out the fir of the conifer trees that are surrounding the opposite end of this periphery. Before I know anything, before I can run off after him suddenly I see twelve bright headlights flicker on. And I’m like, “what the f**k! What’s going on?”

They’re all trucks. All of them are trucks. The boy now I can see because he’s illuminated by some of these lights. He goes up to the driver in one of these trucks and talks to him for a second. He suddenly cranes his body outside of the window and he has a bat and he looks at me and he points it to me like a medieval knight with a sword and he’s like, “That’s him!” and I’m like, “Whoa!” and I just start running in the other direction. I don’t know what’s going on. All the trucks start taking off for me. All the trucks. All I can hear is the roar in the back of me. It’s one of these traumatizing experiences where the rest of your senses just sort of go dead and all you hear is sound and feel just like the vigor of your feet trotting onward. I run to the other edge of the park and I hide in a grove of bushes. I don’t know what’s going on still in this case. I huddle there and I whip out my cell phone. And I call my friend I was living with and I said, “I don’t know what’s going on. You have to come and get me. People are after me. I’m at the edge of Heritage Park,” I told him the cross streets, “Just come and get me.” I’m sitting there in the bushes.

The six cars are rounding the park just constantly. Almost in a perfectly regimented train, looking for me. I could hear the faint whispers and weird search calls where they’re looking for me. I don’t know what to do. Finally, I see a small Miata pull up and I know it’s my friend’s car so I run up to it I’m like “What the fuck,” and he says, “Just get in the trunk.” So I hop in the trunk of his car. As I’m there, my friend, I could hear him leaning against the trunk of the car and the people who are in the trucks come up to talk to him.

As it turns out, Coleman, Alabama is actually the place the KKK relocated after Birmingham. They had caught word that I was a gay man in Coleman, Alabama. They begin to talk with him, my friend. They’re like, “You know man, we’ve heard about this faggot who’s here in town. We’ve been looking for him. He was just talking to this dude.

The guy, by the way, who I’ve been talking to the whole time, was the Grand Dragon's son of the sect of Coleman, Alabama. Of all people to flirt with, of all the people for me to have this romantic fantasy, I choose the Grand Dragon’s son. And he’s sitting there. I’m listening, I’m shaking, I don’t know what’s gonna go on. I fall asleep. I fall asleep! Next thing I know, I wake up.

My friend opens the trunk and it’s just him. We’re out in the middle of the field of goldenrods and he just pulls me out of the trunk; we don’t say anything. We go back to his house, we drag a mattress out to this field of goldenrods and we just lay there and we don’t say anything. The night sky is over us. Eventually we begin to start up a fire and we just talk. The weird thing about this whole experience is it wasn’t something that was traumatizing. It was just me running away from evil. Complete evil. Nothing that was emotionally traumatizing just something I knew I had to get away from. And this all exists. That’s the crazy part of it. It all still exists to this day.

My mom does not know this story so I’m gonna show her this video later and this is how she’ll find out, but I am very glad to have the experience of telling you people this story. And that’s it.

JAIME J: Aaron told his story at a Story Slam on the theme “Busted”. You know, Aaron’s story resonated with our guest, Amber Hikes executive director of the Philadelphia Office of LGBT Affairs, who identifies as queer. Amber’s eyes dropped to the floor as she listened to Aaron’s story and her own memory was resurrected.

AMBER HIKES: We were driving home from the grocery store and this was when we were living in Louisiana and they were outside, just on the road with signs that said horrendous things about black people. And I remember my mom screaming curse words at them and being visibly shaken. And I’d heard about the KKK and learned about them in school but had never seen them until this point. They had their hoods on and everything. There were some people who were not hooded but most of them White hoods and their robes. And my mother was shaken for the rest of the day. And I remember having vivid nightmares that were reoccurring nightmares for the next six years about the KKK. Because up until that point, they had always been this idea right this idea of the past. I didn’t realize they still had an active chapter where I lived in Louisiana. I didn’t realize they were that close to me. I remember vividly I don’t always have the best memory about that time in my life They were one block, this was in more rural Louisiana, but they were one block from what would have been the turn in to my street. And that’s where those nightmares came from. They are physically, geographically close to being able to come into my house and kill me. It was so disturbing. I appreciated Aaron’s story. He did a good job of making it lighthearted, I think. To a certain extent. But to me there was nothing that was lighthearted about the Klan. I had a persistent fear of the Klan until I was 25. It wasn’t until then that they became a joke and saw them for what they were it was pretty traumatizing.

JAMIE J: You know, traumatizing is a word that came up often for the storytellers of this episode. And it amazed me how storytellers like Christian A;xavier Lovehall found a way to use humor to tell a story about their own self discovery. I mean, before he understood sex and gender, he knew what made him happy. The trauma came later.

CHRISTIAN AXAVIER LOVEHALL: Growing up I was never the kid who got a lot of toys. So I was a fan of food and snacks that came with prizes. Cereal that got a toy in it—cracker jacks. But my favorite—my favorite was the Happy Meal. Yeah, Happy Meals! I remember my first Happy Meal, I was about five years old and I was sitting in my Mom’s car—it was in the drivethru. She rides up to the window and the lady asks, “What type of Happy Meal would you like? Is it a Happy Meal for a boy or for a girl?” I didn’t really understand the question but my Mom answers “Girl.” So I get my Happy Meal and I open it up and I see a Barbie Doll. I don’t want to play with Barbie Dolls. So maybe I just got a bad Happy Meal this time.

Second time, open it up: My Little Pony. I don’t want to play with My Little Pony. Third time again she says girl. Open it up: Cinderella. I was really confused because I was like, “These are called Happy Meals, right?” I’m not happy! What’s going on? False advertising, I don’t know. So one day we go inside and I see a young boy about my age. His mom orders him a Happy Meal and she says “Boy.” So I was curious. I watched this little boy open his Happy Meal. And he pulls out a red, black, and yellow Hot Wheels racecar toy. That is a toy. So I figured it out. My mom was just saying the wrong Happy Meal password. I have to say “boy” to get the cool toys. So I told my mom, I said, “Mom. I want a boy Happy Meal.” And she looks and me embarrassingly and says, “Those are for boys only.”

Something inside of me broke at that very moment. I cried hysterically. I got dragged out of McDonald’s that day. And for some time this continued and I feel that at one point my mom got tired of beating me for my tantrums and fits. And she decided to let me get a boy Happy Meal under one condition. When we’re in the drivethru and she pulled up to the window, I had to duck down on the floor because she didn’t want the cashier to see I was ordering the boy Happy Meal for a girl. It was fun at first. I even made a game out of it. But after a while I internalized a lot of selfhatred and shame. I felt like I wasn’t normal. It took a really long time to learn to love myself.

Being seen as the gender you are for many transgender people is an important thing. Many in our community call it “passing.” When you’re a passable male or a passable female. In my case it was when the “she’s” were replaced with “he’s.” But I never really felt that I passed until one night in South Philly. I came outside the crib and I went to the store. I was getting me some dinner. Some ChineseAmerican cuisine: chicken wings and French fries. Maybe an iced tea. Do not forget my loosie. I’m at the store across the street when all of a sudden this police wagon pulls in front of me on the actual sidewalk. Two cops get out and I ask them, “Why am I being stopped?” I was told I was being stopped because I was jaywalking.

That was very strange to me because everybody in Philadelphia jaywalks. OK? That’s usually how you can tell the Philadelphians from the tourists. The tourists, they walk up to the streetlight and wait until it turns green and they cross. We just look to see if a car is coming and we walk. So after he told me that, they pushed me down to the ground and put handcuffs on me. I’m yelling at the top of my lungs, “Why are you doing this? Why am I on the ground?” The cop says, “Oh, you don’t want to be on the ground? Get in the wagon then.”

They throw me in the wagon and close the door. It smells like urine, feces, vomit, blood. I’m in there for thirty minutes. They open the door and let me out they uncuff me. They give me three ticket totaling 360 dollars. One for jaywalking, one for not having an updated address on my ID, and one for disorderly conduct because my screams disturbed the neighbors. Police gave me my food back but it was cold and I had lost my appetite. But that night I knew that I passed as a black man. I knew, also, that to protect and serve didn’t necessarily apply to someone who looked like me. Someone young, black, and male. So, my safety is now a concern. But I will continue on this journey. This revolutionary journey because I do feel that I have a place in hiphop as a transsexual male. On stage I go by the name Words, the poet MC. And I do. Got. Bars.

JAMIE J: Christian Axavier Lovehall is a Black trans man from Philly. He’s known for his poetry, music, and freedom fighting. Under his stage persona Wordz the poet emcee, He’s dedicated his career to art for social change.

KYLIN METTLER: So, I was an excellent tomboy...I beat every boy in my fifth grade call in arm wrestling...I nailed it!

JAMIE J: Christian Lovehall and Kylin Mettler just want to be seen and accepted for who they are...Who doesn’t? But in this case, remaining a “mystery” might have been for the best.

KYLIN METTLER: But by the time I got to college I got really sick of being called “he” because it could make me feel kind of ashamed and not so attractive. So I came up with this great plan. I’d go out and I’d buy a lot of really sexy, feminine clothes that were short and kind of revealing and that would, you know, help me with this problem. But I’d go out shopping and instead of going out to like trendy female stores, I’d end up thrift stores and instead of buying sexy short skirts, I would end up buying overalls. So, my plan didn’t go as I had hoped and I was sort of getting an F minus in college in femininity. And this all changed when I met Clint. See, Clint was not your average gender studies professor. In fact, he was a hitchhiker I picked up on I70 going towards Memphis and he was a little dirty and as soon as I picked him up I regretted it. He got into the car and I started to think about the only ways this could end would be, um, murder or rape or mugging would probably be the best one.

So, we’re driving along and I realize not only this is a bad listener I have ever met or else on a lot of drugs because he asked me the same three questions over and over again. He’s like, “What do you do?” I said, “Well I work at a bronze foundry,” “Well what is that?” “It’s where you make statuary out of bronze.” “But what do you do?” “I... work at a bronze foundry.” “And what is that?” And it went on and on like this and I won’t bore you because I sure was.

The conversation continued and he says, “Are you gay?” And I was so surprised because I answered “Yes” automatically, because it was true. And I then thought, “Shit! Why did I tell him that? Now I’m gonna have to add hate crimes to my list of possible endings to this journey. This is horrible.” Then he leans way back at the window and he kind of sucks his teeth and says, “Dude. I thought you were a chick, dude.” I get that a lot Like, “Dude! You got hair like a chick, dude!” At this point in my life I had a shaved head that was dyed blue with two little pink ponytails in it. And a heart shaved in the back that was dyed red. It was really cool. And I said,

“Yeah, well, I’m a gay artist so that’s how we roll.” And he says, “Dude, you don’t have any facial hair, dude. You only got peach fuzz.” I say, “Yeah. All the men in my family. It’s a genetic thing.”

So we’re driving and he says, “This is so funny. This is hilarious. I’m gonna have to tell the men back at home. I cannot believe when I got in the car I thought you were so hot. I thought you were such a hot chick. But, dude, you are a dude!” And I was beginning to identify with this character, this gay male artist that I have created. I was kind of offended, you know. Like, was I not man enough for him? So then he says, “Do you have a boyfriend?” and I say yes, because it was true! And then he says, “Are ya loyal?” And I realize two things at that moment. One was that I hadn’t solved any problems by pretending to be a boy.

In fact, I probably added to them and it was gonna make a great headline news tomorrow but that wasn’t going to help me at all. And two, that there existed a human being that could have no idea what your gender was and still find you attractive.

So we’re pulling up to the destination and I’m looking at my wallet and I’m looking at him and I’m coming up with really ineffectual battle plans involving elbows and teeth in order to stop him from trying something with me and he gets out and he opens the door and later I would realize that he had stolen from me. He stole my assumptions about gender and about attraction and that later I would end up dating two trans people and identify as one myself. And I would let go of all this need to be he or she and I wouldn’t care what people called me because I would be really OK with who I was. Some people go to like great high mountains to find their yogi teachers but mine came in the form of this dirty old dirtball I picked up on I70 and as he slammed the door, Clint leaned his head back in the car and said, “Dude, you should’ve been a chick, dude.”

JAMIE J: Kylin Mettler is an award-winning storyteller with a degree in sculpture from Rhode Island School of Design.

JAMIE J: Every encounter doesn’t have a funny ending. I’m thinking about that evening in Philadelphia in September 2014. It made national news when a woman and two of her male friends shouted homophobic slurs, and then beat a gay couple in a center city neighborhood.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Yeah, I remember that.

JJ: That beating was so severe that the victims ended up in the emergency room with fractured bones and bruises. The aggressors, well they ended up in jail. Although she was not working for the city at that time, Amber Hikes, who you heard from earlier, is a renowned LGBTQ civil rights activist, and she took note.

AMBER HIKES: Certainly there is plenty of discrimination outside of the community with regard to LGBTQ people and as much as we try to combat that. Even in this political climate we’re in, we’re seeing ramping up of people’s comfort level of being openly discriminatory. I think that’s what particularly concerning for so many of us in the community is that recognizing that these prejudices have existed all along but certain people outside this community are more comfortable being very clear about those prejudices. That’s scary.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: How did you become an activist? How did it become an important career choice but also almost a mission? You spoke a little about teenagers and young people. That’s the most difficult part. Cause I think statistically a lot of teenagers are not welcomed and are kicked out and end up homeless. So how do you decide that you needed to be an activist for these issues?

AMBER HIKES: I appreciate that you brought up youth and young adults in this community. I don’t want to get too much into stats and figures, but I think it’s important to mention this whenever I can. We know that nationally, in terms of youth who are homeless, 40% of them identify as LGBTQ. That is a massive number. It is a profound overrepresentation if we are talking proportionally, that number should only be six, seven, eight percent right? 40% is a profound overrepresentation. When we’re talking about Philadelphia? 54%. It’s an epidemic. We’re only talking about youth that are on the street. We’re not talking about youth that have home insecurity and may be couch surfing or sleeping on a friend’s couches or in and out of transitional housing just talking about youth on the street. So that number is much higher. And that’s terrifying. And to your point, that is due not just in large part but in complete part to youth being kicked out of their homes because they came out as LGBTQ identified. I could go on and on about youth homelessness about what that looks like for generations of kids who grow up on the streets and how that colors and characterizes the rest of their lives.

JAMIE J: And I wonder Amber, how many people see homeless LGBTQ youth and any youth, really as someone who has been robbed of the opportunity to develop in a healthy way in a healthy, accepting environment, to go on and be a productive member of society. They’ve been robbed of this if they have been kicked out of their home because someone feels that they no longer belong there. Which is

AMBER HIKES: Robbed is exactly right.

JAMIE J: That is what’s happening. They have been robbed and they are trying to survive and navigate a hostile environment.

AMBER HIKES: That is it and everything you just said resonated so deeply cause it’s robbed not just of an adolescence or of a childhood. You were robbed of much of your young adult life and possibly your life period. Right? Because your life looks very different when you’re on the street. And we just talked about survival. So, we know these youth get involved in what we call survival crimes. We’re talking about anything from petty shoplifting to sex work. Right? We’re talking about being introduced to drugs hard drugs at a much younger age. And it’s terrifying. When I think about my community, I think about an entire generation several generations, of youth that are our leaders that are having their adolescence and their young adulthood robbed.

JAMIE J: You are listening to Commonspace, a collaboration between First Person Arts and WHYY. And it’s been supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. I’m your host, Jamie J with WHYY’s Elisabeth Perez Luna.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Being accepted by your community is important, but for storyteller Bea Cordelia, the most important thing of all is self-acceptance.

BEA CORDELIA: Shower On the third day of the camping trip you and your father stay at the yard of the house of your father’s cousin Linda and her regrettable husband George, who cracks casually racist and sexist jokes as if they were funny and if they weren’t subtly killing you and all your friends.

Linda lives with George in a cabin. They are dispatching several trees to keep expanding in the middle of the Hiawatha National Forest, a land named after peacemaking Native American leader and federally protected by gun toting white people because even in nature, colonialism is alive and thriving.

You spend too much time indoors over the course of the day but you also hate the mosquitoes and who can really live in the outdoors anyway? You think maybe Theroux was a crackpot. You think maybe this trip was a waste.

You pit the radical potential of the wilderness and its utter absence of structure that you believe conducive to healing and freedom or even utopia against George’s jokes and the rednecks that populate this peninsula. You think maybe nature, like all else, is a commodity for the privileged. If you can’t feel safe amongst the trees and no one, after all, where can you? But you remember all those times when you came up here as a kid to the mythical upper peninsula of Michigan where you first found God and that little seed inside your soul you had already learned too well to bury and aren’t you searching for some shard of yourself that you left out here anyhow? Or perhaps you were never meant to come back to this place after all.

Linda, who you like, pours you a glass of wine and says, “You may be able later, see the Aurora Borealis,” but you think probably not. These things rarely line up right. You have never before seen the Aurora Borealis but you imagine it like an un-ownable shower of particles and light.

On the third evening of the trip, after kayaking down the winding Au Train river, sixteen miles or more, that morning into the afternoon under that hot star sun and after hiking the day before through sand in the bonedry heat and being in more simultaneous places than seems possible most maliciously mauled by death flies and for hours and hours and hours and hours and hours you finally have a place by yourself to shower.

You take a moment when you shut the door to look in the mirror as you strip. Your sweaty, smelly clothes, like failed attempts, fall to the floor. No one can see. The part of your chest above your sports bra has been burned by the hot star sun. Your breasts are still small, but shapely. Later you will inject yourself with estrogen in a tent. For now, you have your hands. You feel your breasts. You trace the pink lines your failed attempts left. You turn on and step into the Aurora Borealis. Particles and light cascade. You realize this is the first time in days you have been naked. You feel yourself naked. You feel your genitals. They are soft in your hand. You feel your shoulders. The skin is tender with red. You feel your feet. They are worn but working. You wash your feet like Jesus did the disciples but it’s just you. Water drips. The spirit moves. The Aurora Borealis would have been beautiful. But you could not have held it in your hand.

JAMIE J: Bea Cordelia is an awardwinning, Chicagobred writer, performer, educator & activist. She’s currently working on the forthcoming web series, “The T” with cocreator Daniel Kyri and distributor Open TV.

JAMIE J: You know, there was a time when it was almost inevitable to associate being gay with those three big letters, HIV. But, with advances in medicine and care, there have been some positive developments, but attitudes and assumptions haven’t changed enough. So, I asked Amber Hikes about her thoughts on the state of things today.

AMBER HIKES: If we know anything about the HIV/AIDS crisis and the epidemic that still plagues us today we know that there was no community was left untouched by that crisis and that is still the case here today. You cannot put blame on a particular community. None of us escaped that crisis. I say this understanding as a black woman. That black women, black men, Latino men, we are still contracting it at rates that are higher than other populations and that’s the reality of that epidemic and pointing fingers at certain communities and spitting that vitriol is what I would call it is not only ignorant but very dangerous. That kind of stigma is what contributes to people continuing to die and continuing to be infected with this disease. That’s what I would say to people that continue to spit that kind of hate and ignorance. None of us have escaped that epidemic, and we will continue to be in that same situation if we don’t raise the level of consciousness and awareness around the disease.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Longevity and survival was not part of the story of HIV in those early decades, though now for some it absolutely is. Mark Davis remembers the early eighties when HIV was first noticed and was described as the “gay cancer” He’s seen a lot of LGBTQ history since then.

MARK DAVIS: Mike Greenly. He was the neighborhood kid that told me there was no Santa Claus; there was no Easter Bunny. And there was no Tooth Fairy. He blew my bubble. When I asked my mom about it, we always had those end of the driveway conversations about 25 yards before we get to our house. And each time was devastating. Lots of trauma. And then he told me about the birds and the bees and I didn’t want to believe it. And when mom and I had that conversation I said, “You mean? [Hand gestures]” Yeah. And I didn’t understand why it seemed so gross to me because I ended up later coming out as a gay man so I guess it was more of the bees and the bees and the birds and the birds. So that was the reality of my childhood being shattered in Urbana, Ohio.

In 1981 I remember reading I swear it was a maybe McGraff paper about a gay cancer that was in New York and Los Angeles. And I was in a bathhouse in Toledo, Ohio. How was that going to affect me? Growing up in the closet in a small town, in a small university, we went to parks and bathhouses and roadside rests and bars that might have had just a light bulb to identify where it was with no name. It was a treacherous lifestyle to live. So that was the way I took it at the time and kind of didn’t pay attention until later on in the eighties.

I can say today that 25 years ago Friday will be my 25th anniversary of living with HIV. How about that?! I’ll never forget that day. The Tuesday after Labor Day, the blood was drawn. It took three weeks back then. Now you can almost get it within minutes, the test results. I walked into the doctor’s office, he opened the chart. HIV was written in large letters so I knew right away. I came back to my office and said to my coworker, “John, I’m positive!” and he said, “That’s great! That’s great!” And I said, “John, I’m HIV positive.” He knew I was going for the test but he thought a situation had come out positive that we were working on. He was devastated and I had to take him to lunch to support him rather than him supporting me. We’ve talked about that for years ever since. And that afternoon, I received an award from the Pennsylvania Association of Rehabilitation Facilities. It was so hard to stand there in shock and receive the President’s Award in front of family and friends and coworkers and people from throughout the state of Pennsylvania. Then the staff people from PARF—the association—we took an aerobics class together at 12th Street gym. And I knew about a support group sponsored by Action Aids at St. Luke’s—excuse me, of Saint Mark’s Episcopal Church on Locust Street. And I was able to get right to that group on the first night. Back when half this of the room smoked and this of the room didn’t. And people were dropping like flies.

And I made the decision to go off AZT and I think that was probably the best decision. Because 25 years later, I’m living with it and I’m thriving. I’m getting older and it’s nice to get older or aging things like cataracts... fun.

But I think of Ronald Reagan whose administration, for seven and a half years, said nothing. After the announcement by the CDC on June 5th, 1981. Ironically, Ronald Reagan died on June 5th. Poetic justice? Yes, it was. The next day was D-Day and everybody would say, “Oh, that was Reaganesque.” But I’m proud to say that that part of it is over and the struggle goes on. And I feel blessed having lost so many friends and family. Five people from my small graduating class within a five-year range. We’re alive! And we got mad as hell and said we’re not going to take it anymore. Silence equals death and knowledge equals powers. Thank Act Up for doing what they’ve done and thank all for doing what you’ve done to make it better life for millions of people despite Ronald, Ronnie, Reagan.

JAMIE J: You know the truth is we may always be faced with violence, discrimination, and persecution. But can our actions today make things better in the future? The owner of the Pulse nightclub in Orlando where that tragic shooting occurred has opted to create a memorial on the property. So that we will always remember those that lost their lives, and that’s pretty cool... right on!

You’ve been listening to Commonspace, a collaboration between First Person Arts and WHYY. It’s been supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. Commonspace includes a monthly broadcast, and podcasts available online, at acommonspace.org that’s acommonspace.org it’s also available on iTunes and Stitcher. Please subscribe, and while you’re listening, give us a rating! I’m Jamie Brunson, host and cowriter of Commonspace. Elisabeth Perez Luna is the Executive Producer of Commonspace, and cowriter.

Our Commonspace team members are Producer Mike Villers, First Person Arts’ Dan Gasiewski and Becca Jennings, Associate Producers Jen Cleary and Ali L’Esperance. Our Studio Engineer is Charlie Kaier. Our Archivist is Neil Bardhan. The theme music is by Subglo. Thank you so much for listening.

ELISABETH PEREZ LUNA: Oh, we almost forgot... Cool news coming out of Philadelphia! The LGBT Community has added two more stripes to the iconic Rainbow Flag One Black and one Brown to recognize the LGBTQ people of color.